Here’s what you’ll learn from IBM’s strategy study:

- How an accurate diagnosis of your organization’s most pressing challenge can help you form a coherent strategy to overcome it.

- How developing your strategic instinct to recognize change early and decisively transforming your business rely on unifying your organization towards a single direction.

- How focusing on short-term financial gains is putting your long-term survival and profitability in jeopardy.

IBM stands for International Business Machines Corporation and is a multinational technology corporation with over 100 years of history and multiple inventions that are prevalent today. Its headquarters are in Armonk, New York, but it operates in over 170 countries.

Institutional investors own over 55% of IBM, while around 30% belongs to mutual funds, and individual investors own less than 1%. Since 2020, IBM’s current Chairman and CEO is Arvind Krishna.

IBM’s market share and key statistics:

- Total assets of $28.999B as of September 30, 2022

- Revenue of $57.35B billion in 2021

- Total number of employees in 2022: 345,000

- Brand value of $ 96,992B in 2021

- Market Capitalization of over $130B as of December 2022

Humble beginnings: How did IBM start?

IBM was founded in 1911 as the Computing-Tabulating-Recording Company (CTR) in Endicott, New York, United States.

CTR was the product of three and a half amalgamated companies:

- The Tabulating Machine Company

- The International Time Recording Company

- The Computing Scale Company

- The Bundy Manufacturing Company

The company’s founding was very well-timed. It coincides with the profound shift of the United States’ agricultural economy to an industrial one. At that time, inventions and innovations were introduced at an unprecedented rate, evolving people’s way of life and defining our modern lifestyle.

The company’s success at these times was due to the wide range of products it offered that were in high demand in industrializing economies from time recording clocks and commercial scales to various mechanical data handling systems, tabulating machines.

But it was CTR’s corporate culture and managerial practices that enabled it to pioneer and serve that demand.

IBM’s scammy and problematic birth

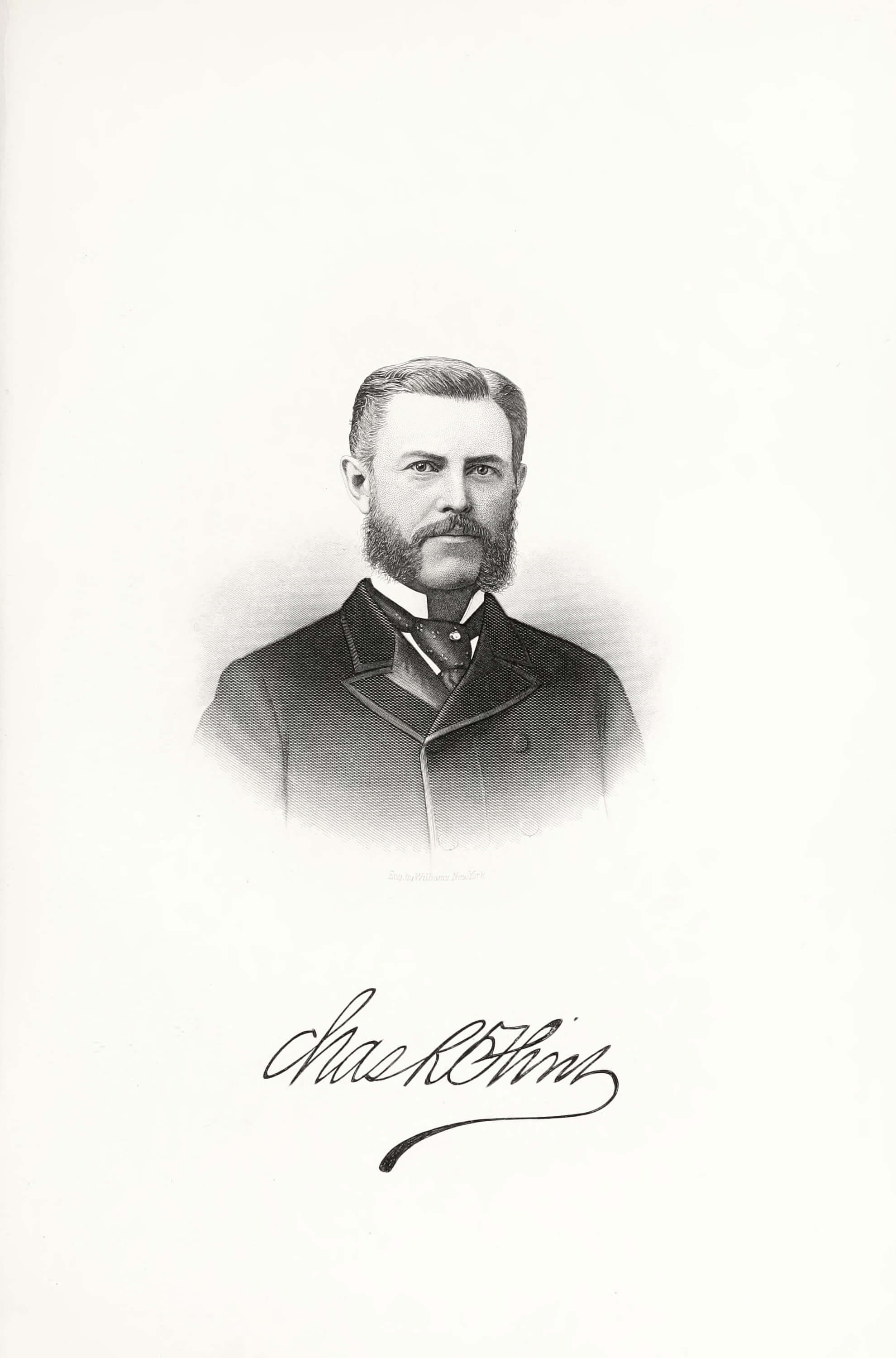

The birth of IBM was the result of the vision and leadership of CTR's first president, Charles Ranlett Flint.

Flint was notorious for combining companies, creating monopolies, and having other people manage them while he simply owned stocks. That’s what he intended to do with the creation of CTR as well.

Here are the companies that formed what later became IBM:

- In 1900, Flint bought The Bundy Manufacturing Company, the inventor of the “punch card” that allowed factories to convert working hours into salaries. The company was quite successful due to increased demand from emerging factories and the founder’s acute business skills. Flint merged the company with the International Time Recorder (ITR).

- ITR was the core of CTR. By the time Flint created CTR, ITR was already a business group and an established player in selling and maintaining time recorders with an international presence. Flint had bought out almost all of his competitors, effectively creating a mini-monopoly.

- The next company that formed CTR was the Computing Scale Company. A marginally profitable company that had created a commercial scale for small merchants like butchers and cheesemakers. It was part of Flint’s vision of mechanical data handling.

- The fourth and last company that formed CTR was The Tabulating Machine Company. The main product of the company was the punch card tabulating equipment that automated parts of a manual and very labor-intensive process. It sped up “data entry,” increased accuracy, and reduced costs dramatically. It was Herman Hollerith’s invention, the second founder of CTR.

The merging of these three and a half companies didn’t make “business sense” at the time, nor was it the result of a careful business strategy.

At least not in the way we mean it today. It was a technical scheme that would allow Flint to protect his investment even if one of the companies wasn’t profitable and he had to sell it. Because, as it turns out, ITR was prosperous, and the tabulating business was slowly growing even though it required huge capital reinvestments. But the computing part of CTR was dying.

As a result, the child of this amalgamation was overvalued by twice its actual value.

This inflated value was supported by a loose argument of “economies of scale” since all these businesses were “measuring stuff.” From its very first days:

- The stock was overvalued

- The company was heavily in debt

- There were a lot of internal clashes

- The three businesses had no synergy

- There was little attention to innovation

- The board of directors only cared about profits

- The customer and employee treatment was poor

In short, IBM was born with some of the worst conditions for any company.

IBM’s coherent business strategy that got it out of the pit

Just three years after its creation, in 1914, the company changed its culture, executive team, and product line.

In ten years, it went through an astounding business transformation.

The move that initiated this transformation was the hiring of Thomas J. Watson Sr. as general manager for the company. The previous leader of the company was simply a credibility mark that Flint had implanted to draw investors. Watson’s influence on the company, however, is so monumental that he is considered the third founder of CTR, who shaped it into IBM.

Watson carried out a series of initiatives that laid the foundation for what would later become America’s largest technology company of the previous century:

- He built a mighty salesforce and a training program called “Sales School” that every salesperson had to graduate from.

- He brought clarity of purpose with frequent communication of goals and performance measures.

- He aligned daily actions with measurable targets that were part of the company’s strategy. He effectively created a culture of execution.

- He created a new line of products in the data-processing industry.

- He implemented initiatives to bring people from the three different divisions close together.

- He improved efficiencies by bringing product developers and manufacturing staff into the same building enabling cross-functional support and information exchange.

- He cultivated a system of shared beliefs and practices that empowered employees to make decisions that were consistent with the company’s priorities.

- He trained customers on how to use their products, gaining valuable feedback and ideas.

Watson spent half of his career as a valued employee of the National Cash Register Company (NCR), where he learned everything he knew about running a business. When he came to CTR, he brought all of his knowledge with him. It included: the development of the salesforce, budget and personnel practices, and even some executives that worked for his previous employer.

Watson was a highly motivated, optimistic, and conservative man of principle. During his tenure, CTR grew and consistently developed its product lines to cover a wide range of business machinery.

He took CTR from a scammy amalgamation to a respectable and healthy organization giving it a new name: International Business Machines (IBM).

Key Takeaway #1: Diagnose the challenge and tackle it with a coordinated strategy

When Watson became general manager, the company was rotten. However, he was ambitious and driven. His approach transformed the firm and affected the company’s journey for many generations. It can be summarized into two distinct steps.

When faced with a crumbling organization:

- Diagnose the most important challenge.

Make an honest swot analysis. Watson found that CTR had a dying division (weakness), a profitable one (strength), and a promising one (opportunity). He based his approach on these findings. - Devise a coherent and executable strategy.

Create a strategic plan that addresses this challenge and coordinates resources. Watson applied all his expertise to developing a salesforce to seize the opportunity he found while internally reforming the company.

Watson practically transformed IBM’s culture into an improved copy of NCR’s culture. His experience fitted like a glove in IBM’s challenges. Some could argue that he happened to be a hammer who found its nail. Others that he found a nail and shaped himself into a hammer.

Whatever is true, his results were undeniable.

IBM’s Golden Period: the strategy and tactics IBM used to penetrate the computer industry

IBM went through the Great Depression and came out of it stronger, wealthier, and healthier.

It also went through World War II, which gave the company an explosive push that was hard to maintain once the war ended. IBM’s activities during WWII were plentiful and… complicated. One thing is certain, among the most important initiatives of Watson was the financial support of every IBMer’s family who went to join the fight and the promise that once the war was over, they would regain their job in the company.

As a result, once WWII ended, the company had more than 25% increased workforce at its disposal while a huge part of its revenue-generating business vanished nearly overnight: the military contracts.

Here’s how IBM faced these new challenges.

.jpeg)

IBM’s corporate strategy against an increased workforce and a vanished revenue stream

Watson recognized the problem from the beginning. His strategy may have been simple, but the flawless execution made all the difference since it wasn’t without obstacles.

The strategy had two key pillars, both focusing on technological advancement:

- Improve, marginally, current products whose demand was still high. The strategic objective was to expand sales on those product lines to generate immediate cash and keep the business floating.

- Invest in R&D of advanced electronics, a new technology that wasn’t fully understood nor ready to be commercialized. This was a necessary bet for the future of IBM.

It was obvious to Watson that the company should, one way or another, lead or at least ride a new wave of innovation and technological advancement. And that wasn’t possible with the company’s current product lines, internal structure, and culture.

The technological and business transformation that IBM went through was an undertaking that few high-tech companies have managed to pull off. Especially when so many stakeholders’ survival is dependent on the company’s well-being. Shareholders, banks that had provided loans, and employees were all highly incentivized to keep the status quo as is and fight against the transformation. “Since we’re selling, why change?” they thought.

This kind of resistance is typical when industry-reshaping technology emerges. Kodak went through the same but, unlike IBM, succumbed to stakeholder resistance, retained its status quo, and eventually died.

IBM’s strategic pivot faced a list of major challenges:

- The best minds in advanced electronics were not working at IBM.

- Advanced electronics was a relatively new industry that nobody could really understand or predict what problems it would solve and what use businesses would find in it.

- New and strong players emerged while old rivals were still actively competing. Remington Rand was an old and active foe while researchers were leaving universities to start new companies and develop systems for the U.S. Army like ENIAC. The reason was that the US government was issuing funding programs investing millions in this new technology. Whoever demonstrated enough expertise and promise was winning the funding, conducting research, innovating, and reaping the benefits.

- Sales resisted the new technology, clinging to its old and tested practices and propositions. In other words, sales and engineering weren't aligned.

The tactics IBM implemented to overcome these challenges and not only survive but also transform as a business in a record time are numerous. Since we can’t really know every single one of them, we’ll go through some of the most important events and principles that enabled the company to devise the solutions it needed.

How IBM overcame the challenges of its strategic pivot

The event that marked IBM’s transformation and sealed its strategic pivot was Watson’s son, Tom, entering the business.

Tom was a bright and ambitious young man who, with the help of his father’s influence and a series of chance events, became IBM’s Executive Vice President at the age of 33.

Tom understood the emerging new technology, and so he led that part of the business. On the other hand, Watson didn’t understand how it worked, so he focused on the more familiar, traditional and still revenue-producing product lines. The two clashed regularly and intensely on many issues. But it’s important to mention that their arguments were never focused on whether IBM needed to transform and adopt advanced electronics. They agreed on that part. They clashed only on the cadence of the transformation and the policies they put in place.

This distinction is crucial because it reveals that the company wasn't divided at its core, the direction everybody moved was the same. The clash between the old and the new was extremely productive because:

- The company started building critical mass in electronics by reinvesting earnings and rental cash flow. It didn’t rely on government funding, but rather it developed its capacity slowly and safely.

- In order to catch up with the industry’s velocity with its bootstrapped approach, IBM’s advanced electronics department had to do things differently. So it cultivated a culture of transparency and accountability where information flowed freely.

- The 604 Electronic Calculating Punch, the world's first mass-produced electronic calculator, was IBM’s first highly profitable product that came out of this approach.

- The firm used its active customer network to understand customer needs and prioritize improvements on the data processing machines. Thus it created machines with validated demand.

- The whole process enabled IBM to create “an infrastructure of knowledgeable customers, salesmen, and servicemen for electronic computers.”

As soon as the 1950s came, IBM entered the electronic computing market and became a highly competitive player. After that, it changed its strategy, took on larger computer projects, and became more dependent on federal funding to offset the associated risk.

It continued to accumulate knowledge and expertise, improving its processes and products.

Key Takeaway #2: Develop your strategic instinct and adapt fast

Develop your ability to recognize change and quickly transform your business to respond to it. To perform a successful business transformation, unite the organization towards a single direction.

If the need for change is clear at the top, it’s a matter of implementation and policies. It’s not easy, but it’s far more successful to lead a united organization than a two-headed one. So when you perform a business transformation:

- Define the direction or destination as clearly as possible.

- Align senior leadership with the desired direction.

- Build guiding policies that take you from the old to the new. Don’t simply kill the old, transform it.

- Treat the transformation as an idea worth spreading. Take advantage of your strengths and apply the Law of Diffusion of Innovations.

The decline during the last decade and IBM’s enterprise strategy to return to the top

IBM slowly but surely started shifting its business model again in the late half of the past century and the following decades.

This time, the strategic pivot was more fundamental. The company shifted from “components to infrastructure to business value.” In other words, it shifted from manufacturing computers and new technologies to offering IT consulting and integration services.

This is reflected in its revenue percentages by segment. In 1980, 90% of IBM’s revenue was generated from hardware sales. By 2015, the company was generating over 60% of its revenue from services and less than 10% from hardware sales.

However, the journey wasn’t as smooth as in past transformations.

The challenges of the consulting industry that has left IBM behind in the last decade

The shift, this time, was taking place less effectively.

The company was selling fewer and fewer pieces of hardware each year while its revenues from consulting services weren’t increasing as fast. The company wasn’t investing as much in R&D, and it entered the new era of computing with an extreme focus on financials.

In 2006 and in 2010, the company's leadership announced “Roadmap 2010” and “Roadmap 2015,” respectively. These were financial goals that were mistakenly used as strategic guiding policies. And to the company’s detriment, they dictated decision-making on every level.

Here are key facts that indicate this extreme financial focus was a terrible strategy at the worst timing:

- IBM’s new CEO, Virginia Marie “Ginni” Rometty, didn’t enjoy employee support. Due to her merciless tactics and her relentless focus to please the stakeholders, employee morale, and thus productivity, was at an all-time low.

- Revenue was decreasing year over year.

- “Rebalancing the workforce,” AKA layoffs, became a regular quarterly tactic to make the numbers.

- Current and ex-IBMers were losing faith and becoming less and less content with leadership.

- Despite the lack of growth, stocks continued rising, paying dividends and high Earnings Per Share (EPS). That was the result of “financial gimmicks” like massive stock buybacks or stashing assets and profits outside of the US to avoid taxes.

- Extreme focus on cutting back costs. Using overseas “global delivery skills,” AKA cheaper workers and even docking 10% of salaries to offer training to employees while charging high-end prices for IBM’s services.

But you can only cut costs for so much and save that much. There is a limit to how much cost-cutting you can do until you hurt operations and production. And IBM reached that limit well before 2015, the year “Roadmap 2015” was promising $20 EPS.

By the end of 2014, the company had amassed a huge debt, its hardware profitability had taken a nosedive, its margins had declined, the executive leadership forwent their personal annual incentive payments for 2013, and it abandoned the Roadmap.

To save the company, leadership had to come up with a radically different strategy. And it did. The 5 “imperatives” strategy was much more attractive to all the stakeholders and would prove to be much more effective.

IBM’s 5 imperatives and its strategy to recovering its past glory

IBM’s biggest weaknesses in the first one-and-a-half decade of the current century have been financial performance and strategic blunders.

But if it had no strengths to leverage, then it wouldn’t be alive today. And its size is one of them. IBM is huge. For example, as of 2018, the company employed around 378.000 people and commanded one of the largest collections of PhDs in computer science and technology. IBM generates over $50 billion in revenue annually with consistently large profits. In 2017, the company had over $8 billion in cash.

The “five imperatives'' were a strategy that focuses on actual performance and not financial engineering to be successful.

The five imperatives were:

- Analytics

- Cybersecurity

- Cloud computing

- Social networking

- Mobile technologies

The company made several acquisitions to close the competitive gap in all of those focuses while it shifted resources to support those initiatives. As a result, it surpassed its competition with analytics software and its capabilities to manage and analyze massive bodies of data. With a $2 billion acquisition of SoftLayer, it caught up with cloud computing and extended its services to include cybersecurity. A partnership with Apple Computer offered the promise of portable computing and app development platforms lodged in cloud servers. Finally, IBM offered management consulting as much as software services through its social networking focus.

IBM's Strategy has focused even more in recent years, integrating the imperatives into two major pillars: hybrid computing and Artificial Intelligence (AI).

It puts everything under the umbrella term: Digital Transformation.

IBM’s focus on digital transformation propels it into the future

IBM’s future looks promising, and its strategy is putting it back at the center of computers and technology. In January 2018, the company announced its first quarter of YoY revenue increase since 2012.

It focuses once again on delivering value to its customers by addressing the crucial challenges that accompany every digital transformation:

- Managing the increased complexity of heterogeneous enterprise IT environments.

- Extracting valuable insights from available data.

- Sustaining operational competitiveness against disruptive market changes.

- Increased cyber threats and increasing cost of cybersecurity.

- A cohesive end-to-end execution of solutions that address all of these matters.

The way IBM addresses these challenges and chooses to differentiate itself is by adopting a platform-centric hybrid cloud approach paired with advanced AI capabilities. The infrastructure relies on Linux, containers, and Kubernetes as the architectural foundation.

In layman’s terms, the value proposition of the company is the sustainable and accelerating transformation of their client’s businesses and processes through:

- Hybrid cloud that develops ability and speed.

- Tailored and trustworthy data governance respecting privacy and generating data-driven business insights.

- AI-driven decision-making that automates enterprise processes.

- Consistency, security, and compliance.

The company is rapidly growing its ecosystem, enhancing client experience while driving value and innovation with its open-source technologies.

Key Takeaway #3: To succeed long term, focus on developing business capabilities instead of financial returns

Ambitious goals and financial promises are not strategies. They might provide some returns in the short term but ultimately set the company up for future failure. Cutting costs is not an infinite-returns-yielding tactic.

When the industry changes, new trends and technologies emerge, and your competitive advantage won’t be serving you for much longer:

- Make a thorough analysis of the environment. Spot the most promising emerging trends in technology, customer expectations, and markets.

- Perform an internal analysis to define your strengths, weaknesses, and current capabilities that power your competitive advantage.

- Develop a strategy that takes advantage of your current capabilities, develops adjacent ones, and mitigates weaknesses to seize the opportunities you spot.

- Until your new strategy is performing and your competitiveness relies on it, ensure cash flow and sustainability through your current healthy lines of products.

Why is IBM so successful?

IBM’s success over its long history can’t be attributed to a single cause.

In each distinctive phase, IBM demonstrated the qualities that enabled it to thrive and pioneer in technological advancements. One consistent quality that allowed IBM to stand the test of time has been its decisive adaptability, the ability to spot new trends and transform its business in time to lead change.

Its corporate culture of respect and hard work has been the cornerstone of every single one of its achievements.

Growth by numbers

Year